Improvement Opportunity

In April 2020, we noted a large increase in hospital-acquired pressure injuries (HAPIs) in our patients with COVID-19 who were on mechanical ventilation and proned for the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). We had 28 HAPIs systemwide related to proning in March and April 2020 and only one proning-related HAPI in all of 2019. We also noted two patient-handling overexertion injuries in our critical care nurses while they were proning patients during the same timeframe.

Another concern was that proning required five to seven caregivers and significant personal protective equipment (PPE), which was in limited supply worldwide. Proning is often a lifesaving treatment, yet it takes considerable resources and time for an already stretched critical care workforce. HAPIs were seen in patients with low, normal and high BMI. However, patients with high BMI have a higher risk of hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19 and pose an even greater challenge to prone. Our goal was not just to reduce HAPI but to ensure we could offer this lifesaving treatment to patients with high BMI and pregnant patients, while protecting and sustaining our workforce.

With the onset of patients with COVID-19, the use of proning increased exponentially. Prone positioning is an evidence-based clinical practice to improve oxygenation in patients who require mechanical ventilation for the management of ARDS. In a pivotal clinical trial, Guerin et al (2018) provided strong evidence that oxygenation improves when patients are in the prone position for at least 16 consecutive hours. "Mortality at 28 and 90 days was lower among patients in the prone position compared with patients in the control (supine) group (p < 0.001)," Guerin wrote.The best practice from literature was to prone 16 hours/day with swimming position changes every two hours (Bamford et al, 2019; Drahnak & Custer, 2015; Mitchell & Seckel, 2018). A recent study implied there is an increased risk of skin injury and caregiver injury risk from the lateral transfers needed for proning unless lifts or air-assisted devices are used. The literature and internal data show that 27%-50% of patient-handling injuries occur from repositioning patients in bed.

Search for Best Practices

In May 2021, we performed an extensive literature search to explore proning techniques and determine if there was existing information about how to prevent HAPIs in this patient population. The search returned 24 articles, primarily discussing manual proning techniques with no mention of skin injury to patients.

We had successful proning using ceiling lifts in our healthcare system at one hospital but noted a large variation in proning methods at our eight other hospitals. This variation included proning with bed sheets, friction-reducing devices (FRDs) and ceiling lifts. We needed to determine how to provide this treatment in a manner that is safe and efficient for both our patients and our workforce. It was clear that the traditional manual way of proning required significant time and resources, and carried an increased risk of pressure injury to our patients and overexertion injury to our caregivers.

Resolution: Leveraging Safe Patient-Handling Technology

To resolve the challenge, we did a literature search and reached out to colleagues across the country to learn from their experiences. These ideas did not yield solutions to our problems, so we applied for an internal safety grant.

We pulled together an interdisciplinary team who treated the vast majority of patients with COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation during the spring surge in Colorado. The team included critical care nurses, wound care nurses, respiratory therapists, Safe Patient Handling & Mobility leads, performance improvement specialists, nurse researchers, nurse practice leaders and supply chain professionals.

We met virtually and for an in-person half-day facilitated meeting in June 2020. All barriers, current practices and potential solutions were identified by clinicians through brainstorming sessions. We then created action items for all team members to perform over the summer. The clinicians worked with supply chain staff to identify all possible solutions to known barriers and risks to the physical movement of prone and swim positioning. Several ideas came from operating room (OR) spine procedures, where proning has been performed for years.

After trialing and researching all summer, the team met in late August for an eight-hour simulation session with all the proning and positioning equipment identified.

Three simulation rooms were used at Saint Joseph Hospital (SJH), Denver. One used a mobile lift, one had a ceiling lift, and another used a variety of FRD systems. Each room had access to all the additional positioning needs. Each participant needed to be both a patient and a caregiver for every technique. We then immediately met to reach a consensus on the best method to prone, since each site used different equipment and processes and felt confident they had developed the most ideal process. Surprisingly, consensus was extremely easy to reach. The caregivers were especially surprised by how much better they felt as patients who used both the ceiling or mobile lift and an FRD to prone. The vote was 100% for this method with other defined tools for positioning and securing the endotracheal tube.

The team developed a toolkit that included a three-tiered flow diagram, so sites without ceiling lifts in their ICUs had other options, and the supply chain ensured all items were available to order systemwide. Positioning equipment included wedges, fluidizers, foams, tape, aerated mats and OR prone positioners. The toolkit also included videos, job aids and a proning checklist that was disseminated systemwide in September 2020 prior to the second surge in Colorado.

SJH, which had 100% ceiling lift coverage, completely adopted the change to a ceiling lift method by the fall-winter surge. In the spring surge, they used a manual FRD proning system. Good Samaritan Medical Center (GSMC), Lafayette, Colorado, added the FRD after using only ceiling lifts during the spring surge. A DNP student at SJH extracted several data points from Epic to compare outcomes before and after the significant proning practice change.

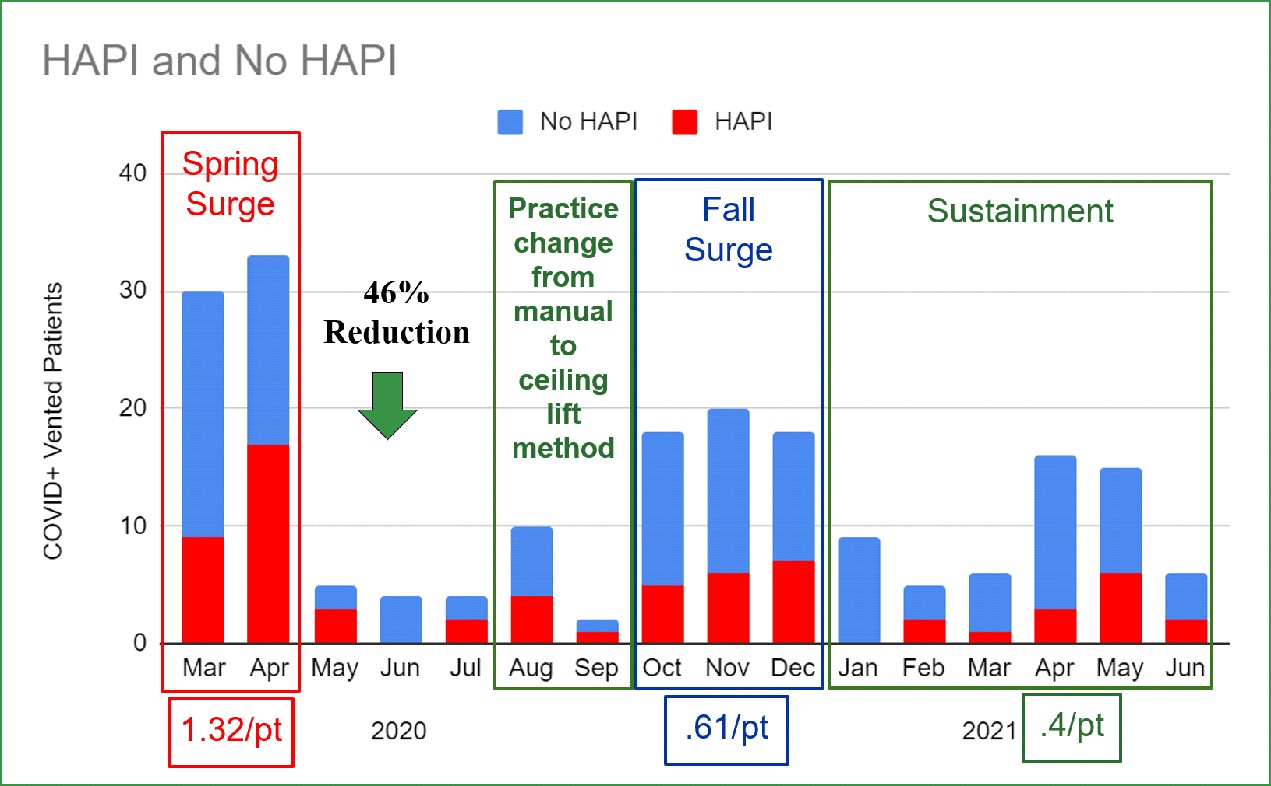

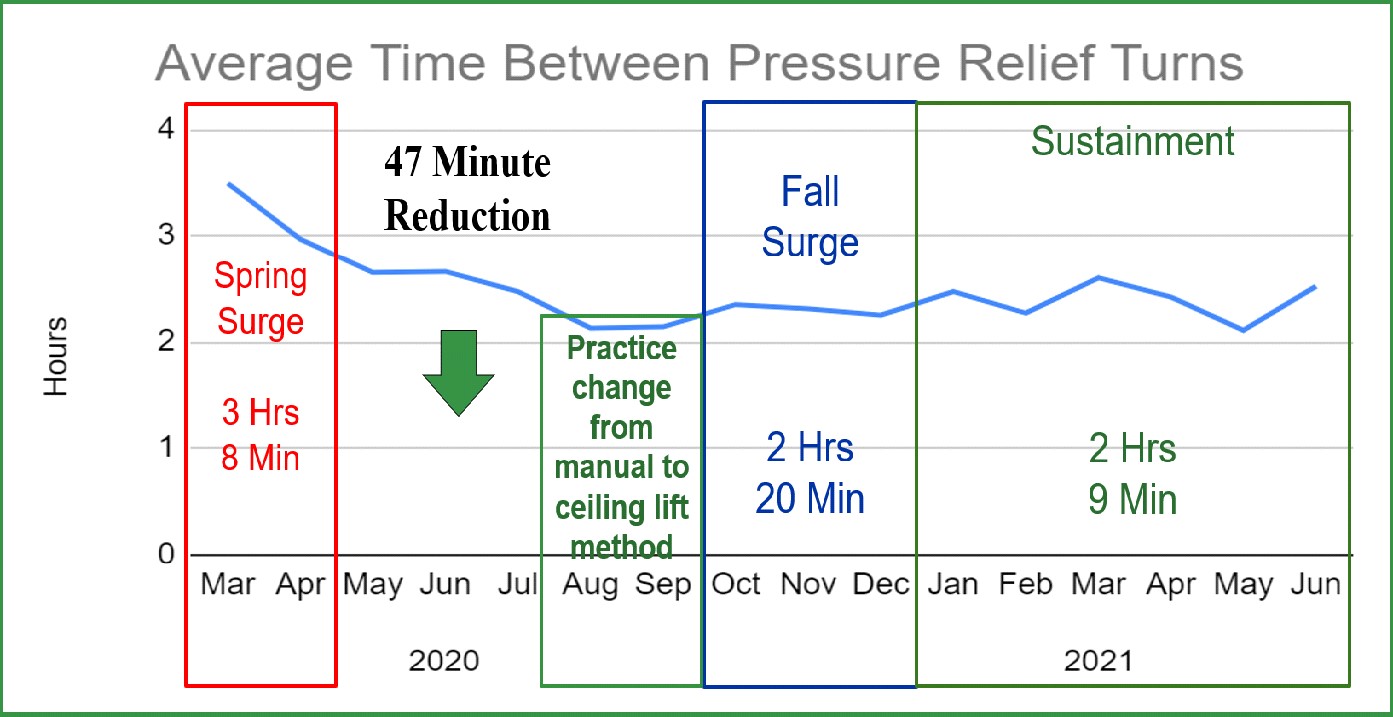

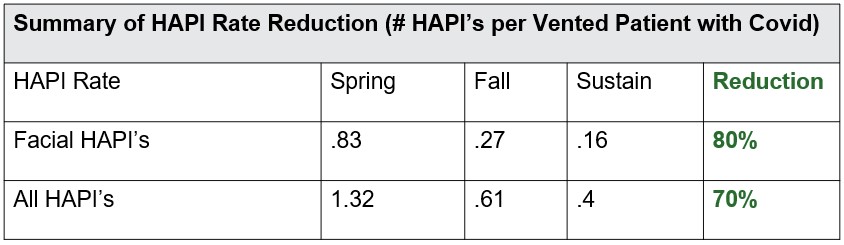

Total HAPI reduction at SJH was 46% after the initial practice change from spring 2020 to fall-winter 2020 and was 70% in sustainment (January-June 2021). Facial HAPI was reduced 80% in sustainment.

Time between pressure relief turns decreased 47 minutes from three hours and eight minutes in the spring to two hours and 20 minutes in the fall-winter, and then to two hours and nine minutes during January-June 2021. This improvement was realized despite increased length of stay; 337 hours, 365 hours, 383 hours respectively and higher acuity measured by mortality; 27%, 52% and 31% respectively.

The Win-Win-Win: Less Patient Harm, Less Caregiver Injury & Less Time!

Pressure injury:

Time and staff savings:

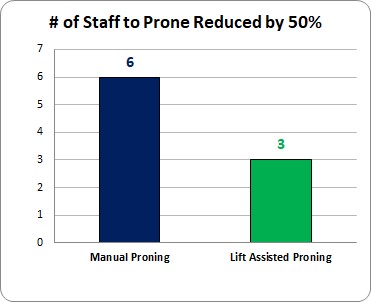

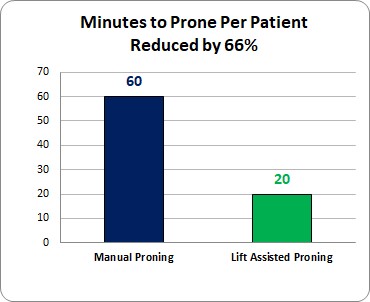

A time study performed at GSMC showed an 83% decrease in the time needed to prone. The number of staff to prone was reduced from six to three, and minutes to prone from 60 to 20, contributing to the 83% overall reduction.

Staff injury:

No patient-handling overexertion injuries were reported for proning patients when staff used ceiling or mobile lifts.

Conclusion

Moving to this three-tiered proning strategy allowed us to improve the safety and efficiency of proning regardless if by ceiling lift coverage or by using mobile lifts. This strategy significantly reduced pressure injury for all patients regardless of their BMI. It also allowed us to meet our other goal, which was to make proning possible for pregnant patients and patients who are 400+ pounds with a BMI in the 60s when many facilities had this BMI as a contraindication. Sites with ceiling lift coverage in their ICUs reduced the time to prone by 83% per patient. This process has been fully adopted at both SJH and GSMC even with the passage of time, stress, turnover and a high percentage of travel nurses.

Just the time savings for this process allows our staff to perform other vital patient care needs while staying healthy and at work. The patient and workforce safety benefits of this enhanced method of proning demonstrate that the patient lifts, initially purchased to prevent workforce injury, also prevent patient injury and improve both the safety and efficiency of care delivery. The very same friction and shear force that cause injury to our caregivers also can injure our patients' skin. The technology that significantly reduces or eliminates friction solves both problems. This body of work also led to recommending the new process to cohort ICUs during COVID-19 surges in areas with ceiling lifts, when possible.

Since proning remains a key strategy for the treatment of ARDS, this process is now a part of onboarding at SJH and GSMC and continues to this day. This strategy is an example of how the urgency of the pandemic led to some rapid advancements that will continue to benefit our patients and caregivers for years to come.

AACN offers the following resources for prone positioning:

- AACN Practice Alert: Manual Prone Positioning in Adults: Reducing the Risk of Harm Through Evidence-Based Practices

- Webinar: Reducing Harm: New Practice Alert on Adult Prone Positioning

- Article: Pressure Injury Prevention in Patients in Prone Position With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and COVID-19

- Article: Nursing Management of Prone Positioning in Patients With COVID-19

- Blogs: Tips When Performing a 12-Lead ECG on a Prone Patient and Enteral Feeding in the Prone Position

Continual improvement is critical to care delivery. Staffing shortages remain a significant issue in healthcare. We need to continue to think innovatively and foster the use of technology, such as safe patient-handling equipment, to improve quality and efficiency.

What other strategies do you use to protect patients that also protect caregivers?

Are you sure you want to delete this Comment?